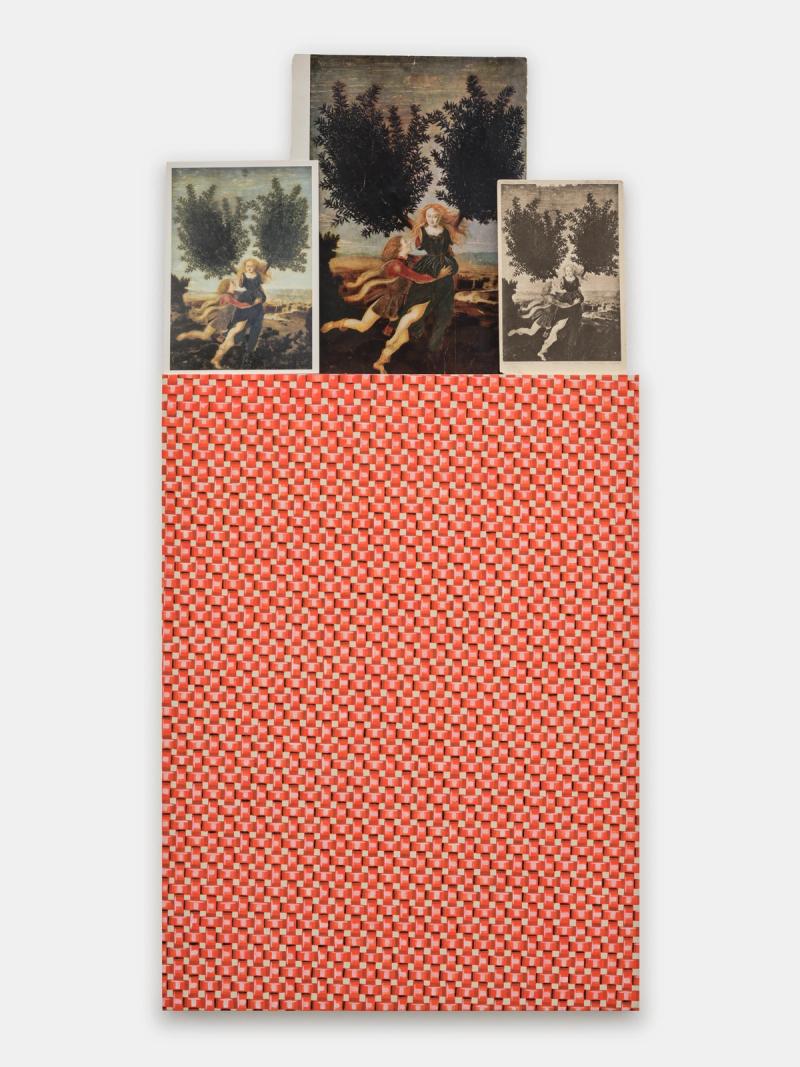

Every week for the past fifteen years, Caitlin Keogh has received images in the mail. Most often they arrive as postcards––sometimes a single card, other times in batches of two or three. Occasionally she gets a big envelope with clippings from museum catalogs and art books. The pictures reflect the taste and expertise of their sender, a specialist in nineteenth-century Realism who Keogh befriended in art school. Many images are too obscure to be online; none of the batches would populate the same Google image search. One week, a postcard of Guido Reni’s painting of Atalanta and Hippomenes arrives; the next, a card of Pollaiuolo’s painting of Daphne and Apollo; then Henry George Hine’s 1850’s illustration of The House that Jack Built; then a Picabia drawing of two people reading, and so on. The connections among the pictures are personal to the life of the sender and to his relationship with Keogh through art: images from their visit to the Met, what came to mind when they were texting about Joe Brainard’s collages, recent discoveries on a trip to Brazil that he thinks Keogh would like. The exchange is an ongoing conversation, largely without words, and a remarkable act of devotion between friends. Perhaps because of that relational trust, Keogh’s growing collection of images foregrounds the intuitions and the desires art evokes when shared with others.

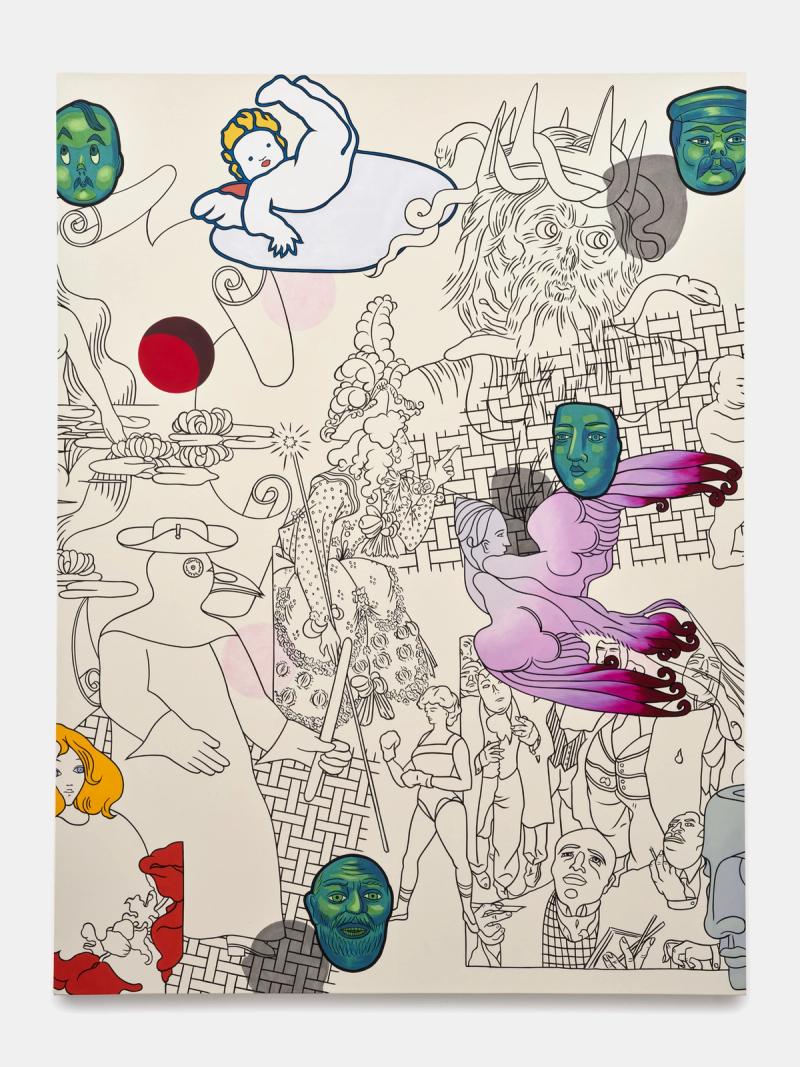

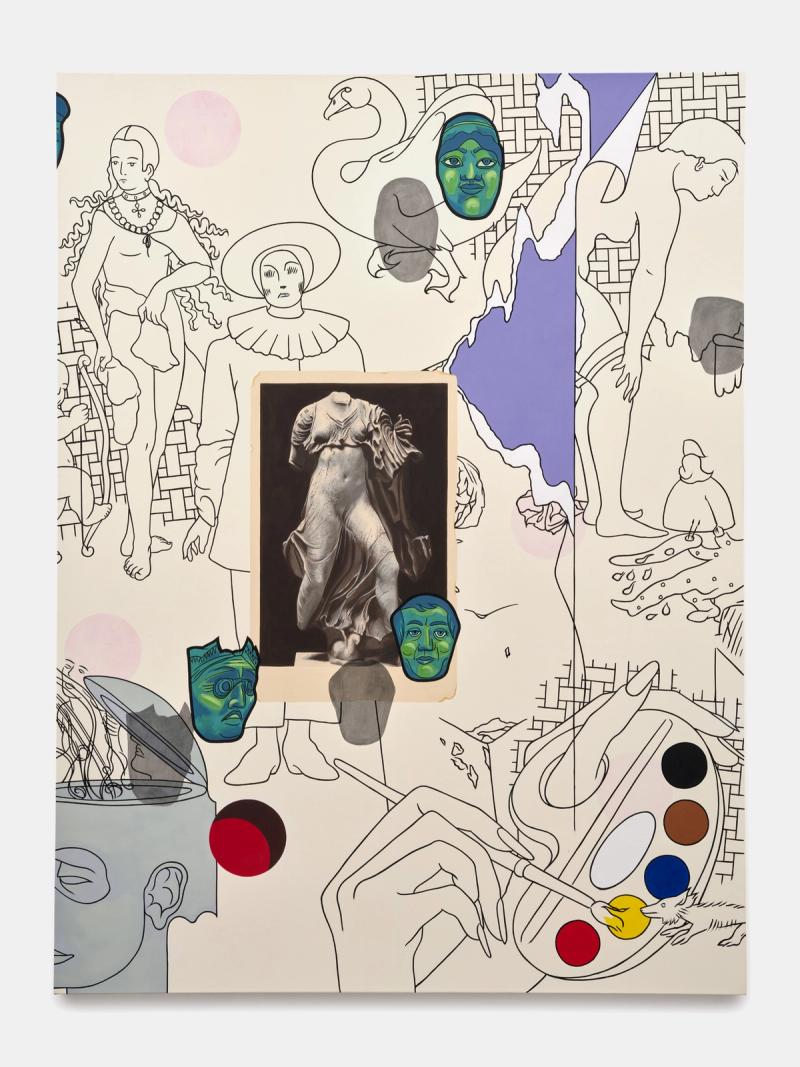

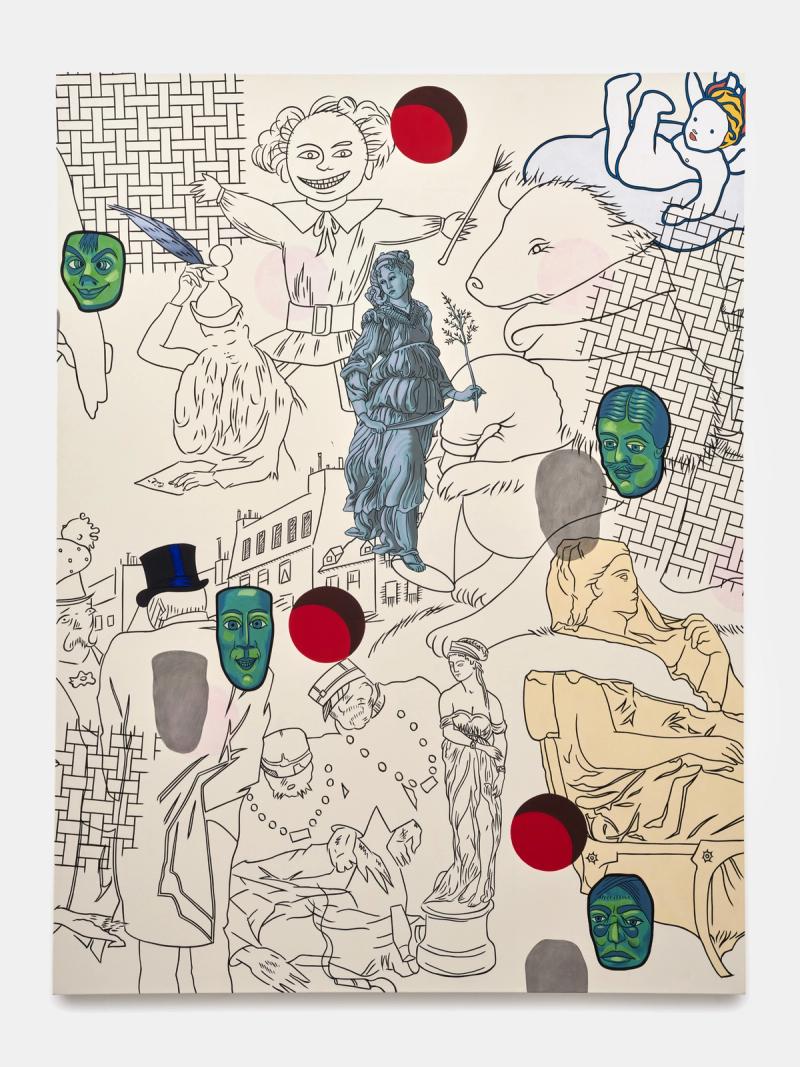

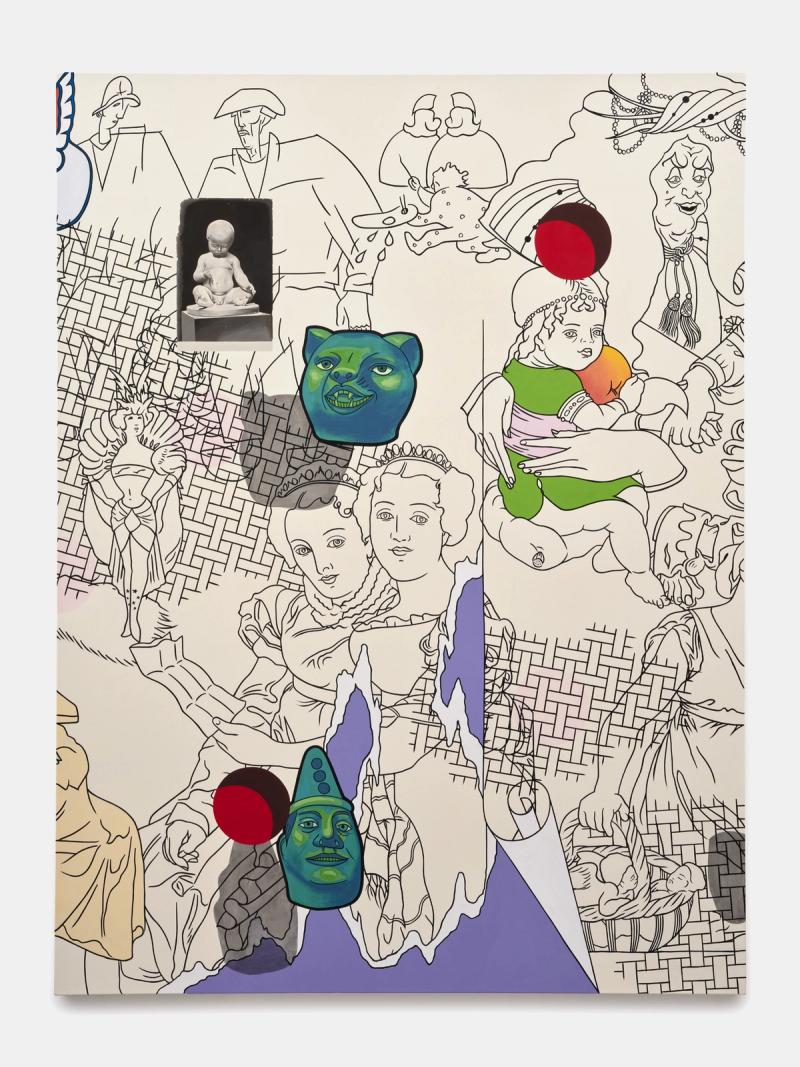

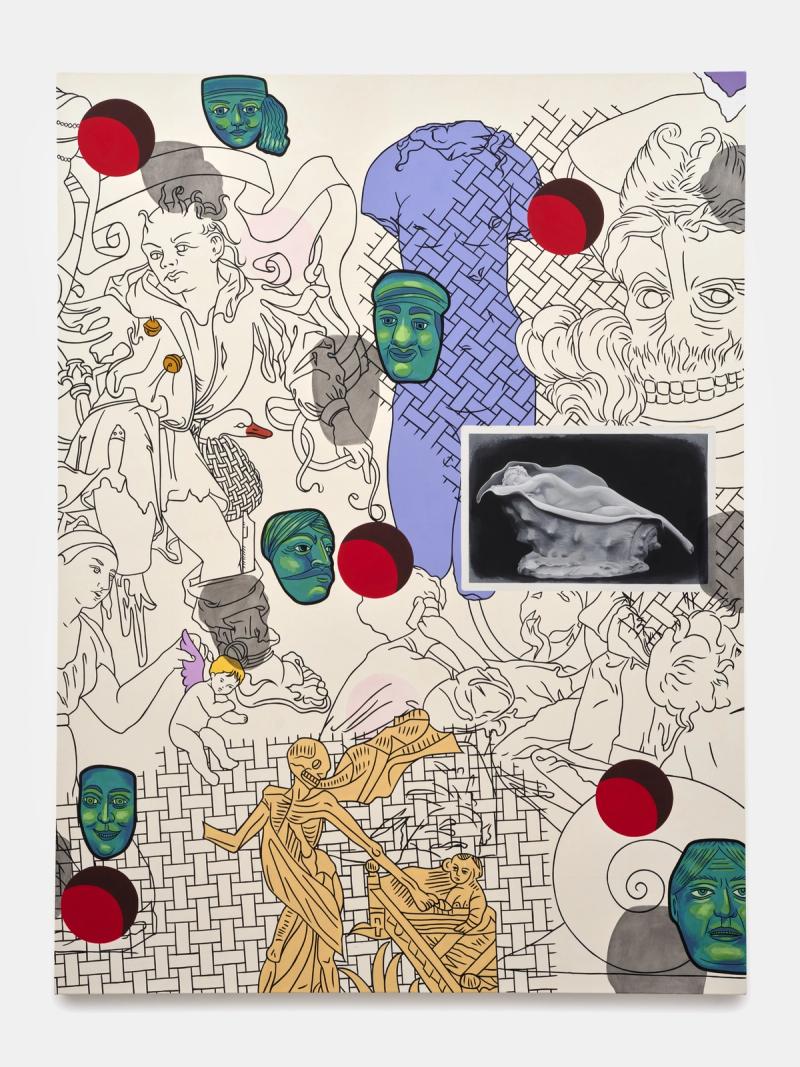

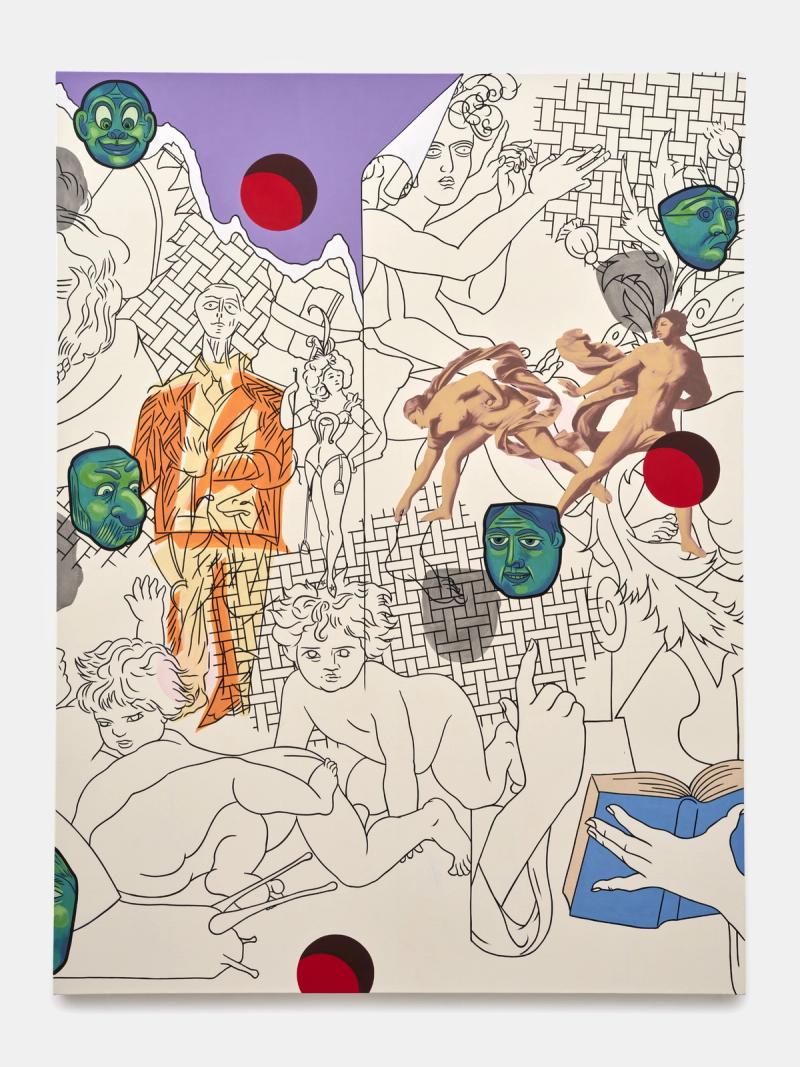

Keogh’s fourth solo exhibition at Bortolami, titled Procession, is itself a generous conversation and act of devotion featuring a cavalcade of images unfurling over eight paintings. To make the works, Keogh pored through hundreds of the images mailed to her, searching for ones whose emotional tone she was drawn to. She looked for unfamiliar images, unburdened by iconic status or overdetermined historical narratives that felt open to interpretation. They were pictures that, to many people in our era of media saturation and aesthetic amnesia, could only be described loosely as “classical” or “historical,” making their beauty, mystery, or strangeness all the more potent for generating associative responses. Keogh was interested in how the images in her pile spoke to her and to one another, and, in turn, how they would speak to viewers encountering them through the language of her painting.

Works

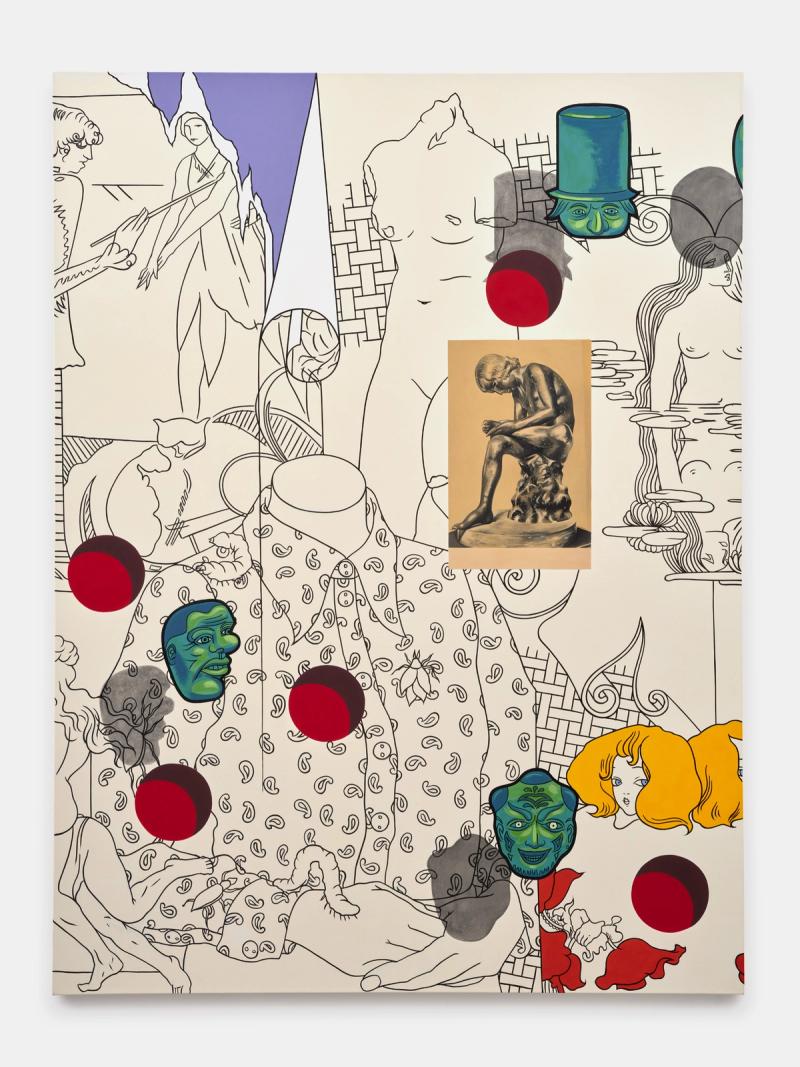

Procession Painting, Plague Doctor and Bird, 2024

Procession Painting, Nereid and Swan, 2024

Procession Painting, Police and Painter, 2024

Procession Painting, Workers and Sisters, 2024

Procession Painting, Man and Sleeper, 2024

Procession Painting, Atalanta and Reader, 2024

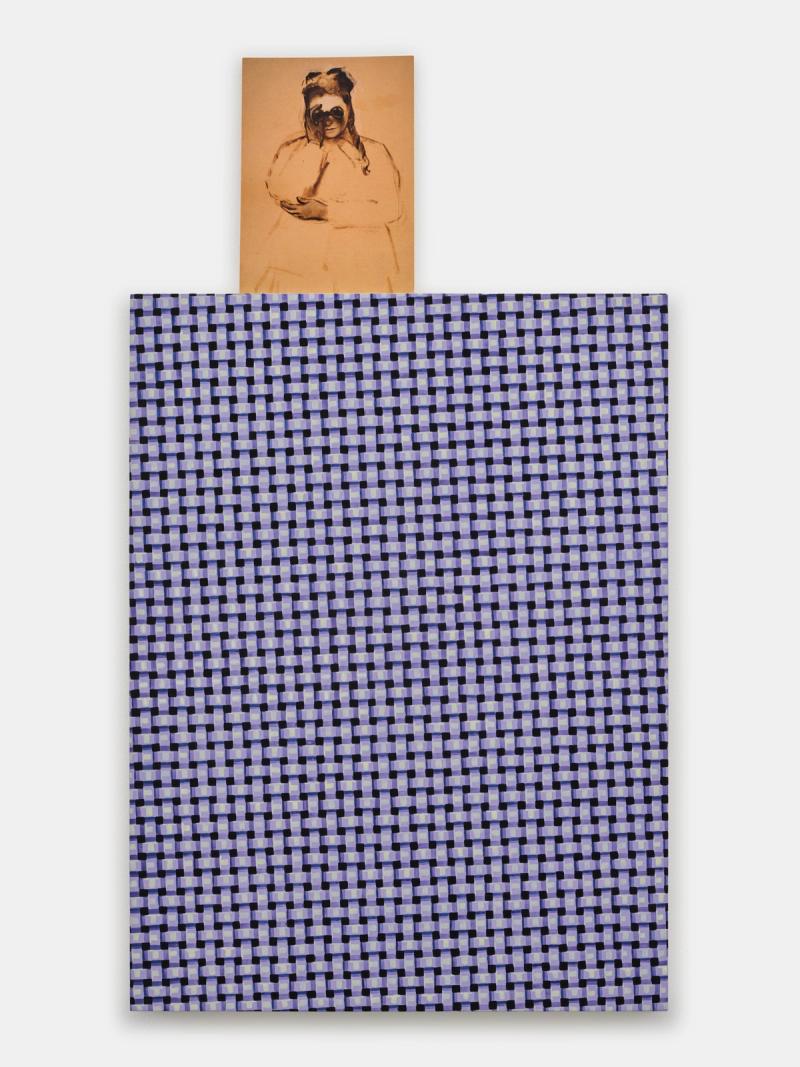

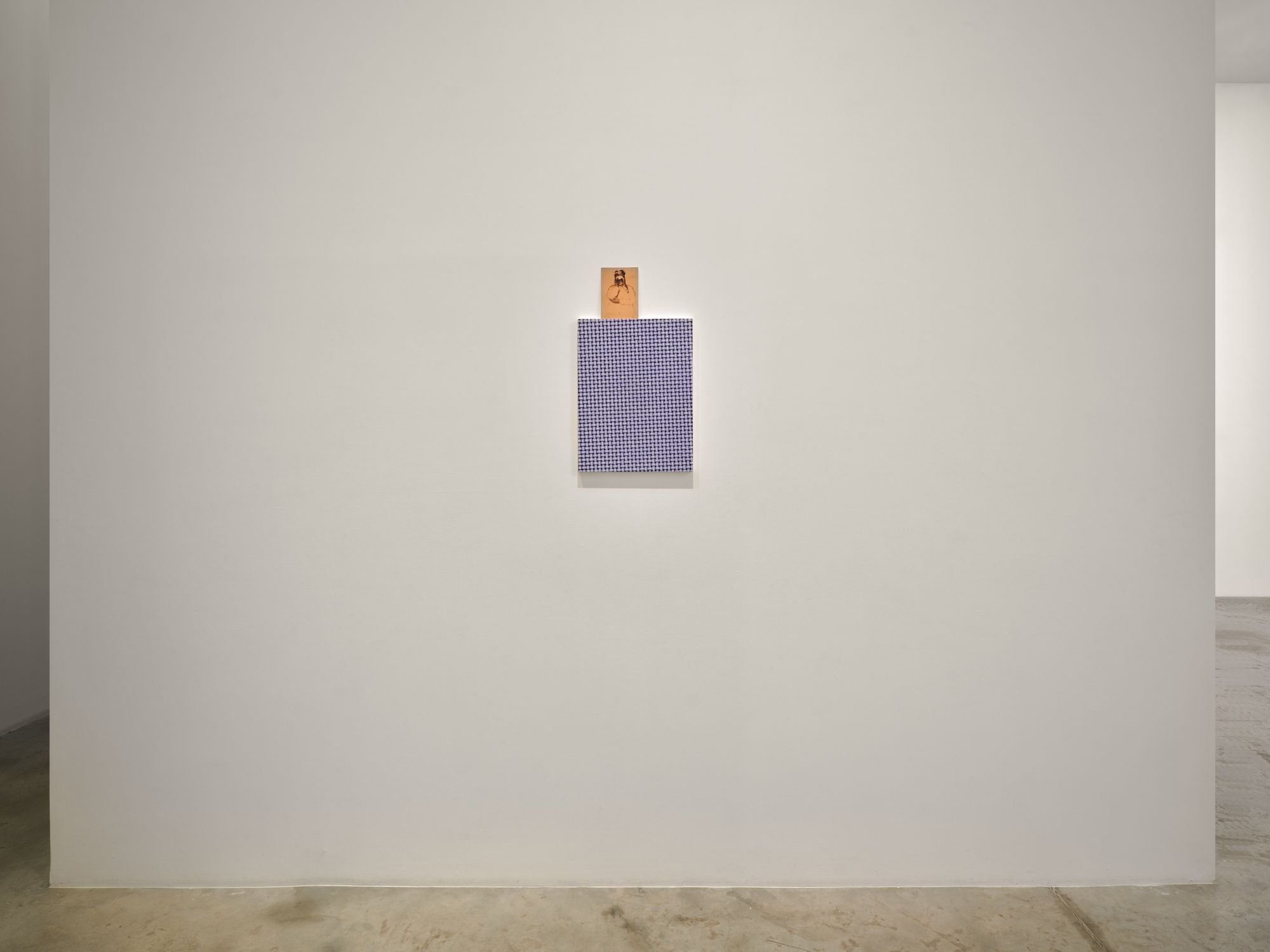

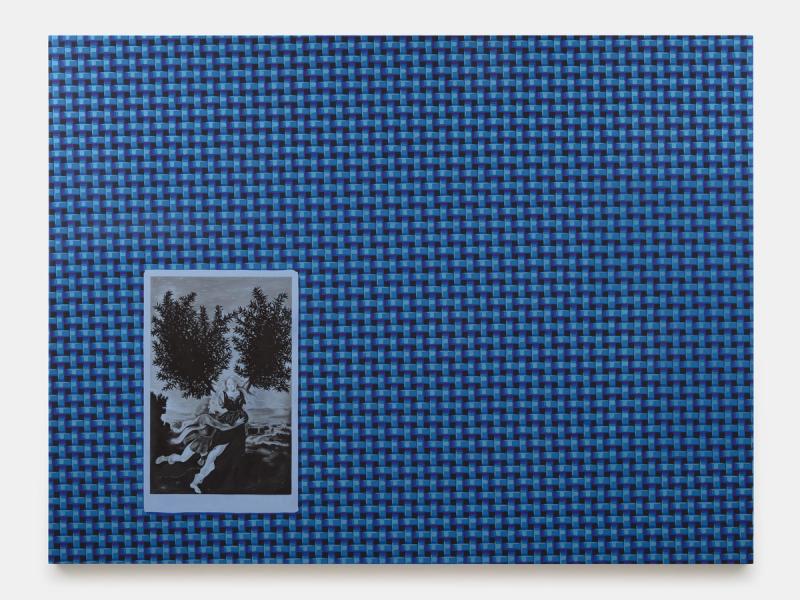

Matrix Painting, Daphne, 2024

Matrix Painting, Three Daphnes, 2024